| Back

to previous page |

~Past Event ~ 2005 Information |

Tsugaru Nuri (Tsugaru Lacquer ware) |

The Tsugaru Nuri lacquer ware exhibition featured a Tsugaru Nuri crafter together with background on Japanese lacquer ware and explanations on the specific tools and techniques of Tsugaru Nuri, the lacquer ware of the Tsugaru District of Aomori Prefecture, the northern-most prefecture of Honshu, Japan. The Tsugaru Nuri exhibition featured lectures, demonstrations, and explanations by Mr. Ken'ichi Suto and Mr. Anthony Rausch. Mr. Suto is an award-winning lacquer craftsman of Tsugaru Nuri. Mr. Rausch is a noted Tsugaru District Researcher and author. Visual displays of Tsugaru Nuri as well as of a wide-range of Japanese lacquer wares were on exhibit. And explanations on the history, techniques and beauty of Japanese lacquer ware, with a specific focus on Tsugaru Nuri lacquer ware were presented. |

| ~ Thanks to Mr. Rausch for the text content. ~ |

|

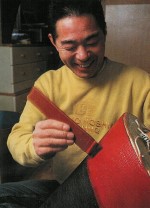

Mr. Ken'ichi Suto" |

| What is Japanese Lacquer ware? |

The luster and durability of Japanese lacquer ware is a combinative function of lacquer and lacquering technique. The lacquer, urushi in Japanese, originates in the sap of the lacquer tree, a poison sumac (Rhus vernicifera stokes; similar to Rhus toxicodendron in North America). The main component of urushi is urushiol, the chemical composition of which is C21H32O2, making it a mild poison. The lacquer is collected in what is called khaki-tori, a process requiring patience and planning. A lacquer tree must grow for ten years before the sap can be harvested, which takes place from June to November, and ultimately kills the tree. One tree will yield just 300 to 350 grams of raw lacquer sap, an amount equal to a medium-sized cup. The lacquer is 'pulled' from the tree by making cuts in the bark, after which the tree, in attempting to protect itself, lacquers the wound closed. In this process, the collector can pull several drops of raw sap. The sap is collected from trees growing in rough mountainous terrain, with the moisture content of the sap varying depending on soil, sunlight and season. As the number of collectors dwindles, raw imports of sap for Japanese lacquer ware have increased to where at present, approximately 98 percent of raw lacquer sap is imported from China. Given time and the right conditions, the lacquer hardens to an impervious surface coating. The lacquering process requires patience and care. The deep lustre of the eventual surface pattern of the best lacquer ware is a result of many layers of lacquer, each applied and allowed to harden before application of the next layer - all of which are then sanded through to reveal the underlying pattern, and then shined and buffed to yield a shiny surface. |

Back to Top |

| What is Tsugaru Lacquer ware? |

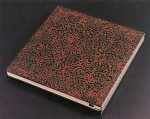

(Contemporary Tsugarunuri; Nanako-nuri)

(Contemporary Tsugarunuri; Kara-nuri)

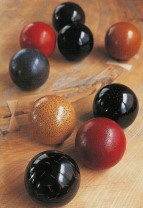

(Tsugarunuri Flower Vase) "Photos Courtesy of Mr. Ken'ichi Suto" |

Tsugaru Nuri is the joining together of base forms, wood is most common, but pottery and metals are common as well, with precious lacquer sap in what were once secretive, yet still relatively unknown techniques, which, through a labor-intensive and time-consuming process of lacquering and polishing, result in a variety of lacquered goods with intricate and inexplicably detailed surface patterns and astonishing longevity. The pieces range from the ordinary and everyday - chopsticks, trays and bowls - to the extraordinary and prized - a zataku, the Japanese-style low table or a fubako (stationery box) and suzuri (calligraphy set). From the standpoint of craft tradition, Tsugaru Nuri is a piece of lacquer ware based on (1) the Tsugaru lacquering techniques, (2) any one of the four designated Tsugaru lacquer ware patterns, (3) the traditional Tsugaru coloring, and (4) being of the Tsugaru District in origin. The artistic and complex character of the four contemporary representative patterns of Tsugaru Nuri are varied: the mysterious and random multi-colored speckling of kara-nuri; the minute uniformity of the circle-patterned nanako-nuri; the subtle design and soft shading of monsha-nuri; and the combinative intermixing of these styles in nishiki-nuri. It is in the multiple applications of lacquer, as many as forty for a single piece of Tsugaru Nuri base lacquers, then overlying pattern lacquers, and finally surface lacquers, that the complex patterns, deep tone and lustrous finish of Tsugaru Nuri emerge. The colored patterns of Tsugaru Nuri are dictated by the thicknesses of the pattern-lacquer layers, created with a spatula-like tool in kara-nuri, dried rapeseed spread on the surface in nanako-nuri, and likewise burned rice husks in monsha-nuri. After the final applications of the surface lacquer, these patterns are brought out with sanding and polishing, which works down through the layers of lacquer, revealing the pattern that lies in the layers of lacquer underneath. Some have called Tsugaru Nuri the fool's lacquer ware, as only a fool would work so hard for one piece. Others claim that this designation rather reflects the purity, a foolish purity of honesty of traditional technique and diligence of hard works of the Tsugaru Nuri crafts worker. | |||||||||||||

Back to Top |

| Tsugaru Nuri Craftsman, Ken'ichi Suto |

|

|

|

| "Photos Courtesy of Mr. Ken'ichi Suto" |

Lacquer craftsman Ken'ichi Suto was born in Hirosaki City, Aomori Prefecture in 1957. At age 21, Mr. Suto took up study at the Ishikawa Prefectural Wajima Nuri Craft Technique Research Facility, where he would continue to learn lacquer techniques over the following six years. From the early 1990s, the unique character and high quality of Mr. Suto's lacquer work has been consistently recognized in exhibitions and competitions throughout Japan. He has won awards locally, taking a prize every year since 1995 at the Tsugaru Nuri Superior Works Exhibition, as well as nationally, including top prizes at the Tokyo Dome Tableware Festival in 2001 and 2004 and the National Traditional Crafts Exhibition Chamber of Commerce Top Award in 2004. Mr. Suto was certified as a Traditional Crafts Master in 1999 and was recognized as a Technical Expert in the area of Lacquer ware Crafts by the Japan Lacquer Crafts Association in 2003. In that same year, he was chosen to produce awards medals featuring Tsugaru Nuri lacquer ware patterns for the 2003 Asian Winter Olympics, held in Aomori Prefecture. Mr. Suto continues to produce lacquer ware pieces for everyday use at his Ken Urushi studio in Hirosaki City. Mr. Suto will be on hand to demonstrate the specific techniques of Tsugaru lacquer ware, as well as discuss Japanese lacquer ware in general. Together with the tools and the techniques of the Tsugaru lacquer ware craftsperson, he will serve as a source of knowledge about Japanese lacquer ware, while illuminating the techniques and special characteristics of Tsugaru Nuri lacquer ware. |

Back to Top |

| Tsugaru District Researcher, Anthony S. Rausch |

Currently Foreign Lecturer in the Faculty of Education at Hirosaki University, located in Aomori Prefecture, Japan, Anthony Rausch first came to Japan, and the Tsugaru District, in the late 1980s. A native of Minnesota and a graduate of the University of Minnesota, Rausch completed his Master's Degree at Hirosaki University, Faculty of Humanities and is now nearing completion of PhD studies at Monash University (Australia). He has published on a wide-range of subjects concerning rural Japan, including volunteerism and civil society, education and local media, and local arts and crafts and cultural commodities in local cultural and economic development. He has published books on Aomori, including The Birth of Tsugaru Shamisen Music: The Origin and Development of a Japanese Folk Performing Art and A Year with the Local Newspaper: Understanding the Times in Aomori Japan, 1999, and contributed to The Formation of Tsugaru Identity and Wearing Cultural Styles in Japan: Concepts of Tradition and Modernity. Mr. Rausch will be on hand to outline Japanese lacquer ware and provide specific explanations on Tsugaru Nuri in English. From the history to the techniques to the contemporary status of lacquer ware and Tsugaru Nuri, Mr. Rausch is looking forward to interesting discussions with festival visitors. Mr. Rausch will also be giving a lecture(s) on Aomori Prefecture and the Tsugaru District, the far-north corner of Honshu. Aomori Prefecture and the Tsugaru District, located in the northern-most corner of Honshu, are too many, an unknown area of Japan. With a complex and contested history and two unique and symbolic dialects, Aomori Prefecture remains a mystery to many Japanese. Mr. Rausch will touch on the history, the tensions, the isolation and the contemporary struggle of Aomori, focusing in particular on the western half of the prefecture, the Tsugaru District.< |

Back to Top |

| A brief History of Japanese Lacquer ware. |

The sap of the lacquer tree was first used in Japan centuries before the history of Japanese lacquer work as such can said to have started, evidenced in the findings of lacquer in Jômon (ca 10,000 BC ~ 300 BC) archaeological sites. It was, however, only after the introduction of Buddhism in the middle of the sixth century that lacquer ware became a common medium for works associated with religious practices. Such religious function continued into the Heian period (794-1185), but lacquer ware also took on an indication of social status for the aristocratic elites. While the elites of early Japan had long fostered the arts, the domestic wars that accompanied the transition from the Heian to the Kamakura period (1185-1333) left them so impoverished that they no longer had the means for artistic support. With the power of the Imperial Court weakened, the large daimyô, the feudal clans situated throughout Japan, invited the now-impoverished artisans to their provincial seats. In these outlying areas there arose localized centers of culture, which in many cases fostered production and development of lacquer ware. The Momoyama period (1568-1600) saw a rise in the notion of functional beauty, marking the starting point of what would become the core notion of Japanese arts and crafts, and leading to the dual production of lacquer works which were decorative on the one hand, together with production of new practical lacquer items for everyday use on the other. The Edo period (1600-1868) provided a backdrop for great development in Japanese lacquer ware. The Tokugawa shôgunate and succeeding generations of feudal elites summoned lacquer artists to their court in Edo and provided them with handsome commissions for the production of highly original lacquer ware pieces. The chief concern of the lacquer masters of this period was to satisfy the needs of these patrons for ceremonial showpieces. Innovation of style, often a function of development of specific lacquering techniques or use of some unique material, was key to the success of the lacquer master. The Edo period also saw the institution of the sankin-kôtai system, the stipulation that provincial feudal leaders spend alternate years in the Edo capital, providing the means for lacquer ware pieces, as well as a variety of innovative techniques to create them, to be transferred between the Japanese center and the peripheral areas. The result was the emergence of kawari-nuri, or 'changed lacquer techniques,' which developed in the provinces under the patronage of the local feudal families and led to the emergence of distinct local lacquer wares produced with new techniques and innovative use of local materials. The end of the feudal era came with the Meiji Restoration and the Meiji period (1868-1912) which followed brought fundamental changes to the power structure of the nation-state, and subsequently to the meaning of lacquer ware. The daimyo lost their sources of revenue, and thus their capacity for patronage of lacquer ware. The lacquer masters, with their principal means of financial support gone, had to adapt to living off the sales of their work. This was a difficult transition, due not only to the fact that a quality piece of lacquer ware could take months to complete, but also that the demand for innovative styles supported by the patronage systems dropped off completely. Demand for novelty and originality, so important in the Edo, was now replaced by institutionalization and uniformity of both pattern and price. The Tokyo Art School (Tokyo Bijutsu Gakkô) was founded in 1888, and included a lacquer training division. The Nihon Shikki-kai, the Japan Lacquer Association, was established in 1889 and in 1890; the Emperor Meiji (1852-1912) convened the Imperial Academy of Art, an art advisory council which included a representative for lacquer ware. The creation of the National Museums in Tokyo (completed 1882), Kyoto (founded 1889), and Nara (founded 1889) helped foster public interest in the native arts of Japan, including lacquer ware. In the mid-1920s, Yanagi Muneyoshi's (1889-1961) expression of the notion and meaning of Japanese folk crafts brought about a revival of interest in Japanese folk art, sparking awareness of the beauty and importance of local lacquer wares among the general public. In 1927, lacquer work was included for the first time in the annual government-sponsored art exhibition, the Teiten (changed to Nitten). In response to the overwhelming national focus on industry and mechanization that accompanied the period of high economic growth in the decades following the Second World War, the Japanese government took measures to protect Japanese arts and crafts. Under the provisions of a 1951 legislative act, the National Commission for the Protection of Cultural Properties (Bunkazai Hogo Iinkai) was established in 1954. This body allowed for the designation of intangible cultural properties (mukei bunkazai), including, among other things, the traditional techniques of applied arts such as lacquer ware. At the same time, the Japanese Arts and Crafts Association (Nihon Kôgeikai) was established, and has since held annual exhibitions of traditional Japanese arts and crafts. |

Back to Top |

| Varieties of Japanese Lacquer ware. |

There are numerous local varieties of lacquer ware found throughout Japan and currently twenty-two nationally designated traditional lacquer wares. These regional lacquer wares are differentiated primarily on the basis of some aspect of regional representativeness: an aesthetic value such as a particular motif, pattern or color scheme; use of a particular local variety of wood as the base or some local material in the lacquering process; or the application of some specific lacquering technique developed in that locale. As such, these regional lacquer wares can be considered representations of regional identity in Japan's national identity for some, but for the people of a lacquer ware producing area, this identity is clearly of a more regional or local nature. The regional lacquer wares included in the Nihon no dento-kogeihin reference book is (in this order): Wajima Nuri (Wajima, Ishikawa Prefecture): A high quality lacquer refining process and the composition of the clay undercoating produces a durable lacquer ware. A multi-step process, with undercoating based on a local soil, means that Wajima Nuri is community-based with multiple enterprises cooperating in the production, strengthening the sense of local ownership. The origins are in doubt but most agree that the industry is less than 200 years old. Aizu Nuri (Kitagata and Aizu Wakamatsu, Fukushima Prefecture): Extensive documentation places the start of lacquer ware production in the latter part of the sixteenth century, with a peak in production in 1878. Although attempts to reduce prices brought down the quality meant that the consumer base was lost, at present, some 4,000 people are still employed in the production and marketing of Aizu Nuri. Kiso Shikki (Narakawa Village, Kiso-gun, Nagano Prefecture): As with Wajima Nuri, a clay undercoating derived from local sources is a fundamental element in the production of Kiso shikki. The Kiso shikki lacquering techniques are numerous, producing a variety of lacquer ware goods as well as being applied to fishing rods and other fishing gear. Hida Shunkei (Takayama, Gifu Prefecture): The term shunkei is used to describe both the lacquer ware and the technique that produces it. At some point, Hida shunkei became associated with tea ceremony and the industry owes its growth in the Edo period to patronage of the local lord. Hida shunkei can be found in many forms, depending on both the wood form and the tone of the stain and the resulting coloration after the lacquer is applied. Kishu Shikki (Misato-cho, Wakayama and Kainan, Wakayama Prefecture): The commonly accepted origin of Kishu shikki holds that monks produced lacquer ware for their own use, called Negoro-nuri, before production was undertaken full-time due to a dispute within the temple community. While originally used for bowls, modern Kishu shikki includes common household items, based on a variety of wood bases and done in a variety of styles. In addition, wood composites and plastics are being used in order to meet modern demands. Murakami Kibori Tsuishu (Murakami, Niigata Prefecture): Known in China as ti hong, Japanese tsuishu is the technique of building up layer after layer of lacquer and then carving into it. Murakami kibori tsuishu, however, uses a piece of wood carving as a base on which to apply the lacquer. Although the origins are not clear, production is believed to have been undertaken as early as 1400, when Kyoto-based lacquerers settled in the area after being called upon to work on the building of local temples. Kamakura Bori (Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture): As Japan's capital during the period of the same name from the late twelfth to the mid-fourteenth centuries, Kamakura is a great repository of history. Kamakura bori is essentially a highly developed type of wood carving, the quality of which is enhanced by a coating of lacquer. Originally something that specialist woodcarvers engaged in during spare time, serious production of Kamakura bori began in the latter part of the nineteenth century. At present, Kamakura bori is a popular hobby practiced throughout the country. Yamanaka Shikki (Kaga and Yamanaka-machi, Ishikawa Prefecture): Yamanaka shikki started out as an uncoated woodcraft. Originating in the Tensho period (1573-1592), it wasn't until the Horeki period (1751-1764) that lacquering techniques were applied. While pioneering the use of synthetic lacquers and various fiberboards as the wood base in order to compete with the ubiquity and low price of plastic goods, the traditional techniques and materials are still prized. Kagawa Shikki (Takamatsu, Kagawa Prefecture): Also known as Sanuki lacquer, the names refer to a number of types of lacquer ware produced around Takamatsu - all of them different from other types of lacquer ware found in Japan. The origins are in the year 1830, when a lacquerer in the employ of the Takamatsu domain studied lacquer ware of Thailand and China. Tsugaru Nuri (Hirosaki, Aomori Prefecture): The polychrome patterns are the signature of kara-nuri, the most common of the types of Tsugaru Nuri. Dating from the Edo period, various types of lacquer ware have been developed, but they all involve a process of burnishing down through layers of previously applied colored lacquers to reveal a pattern intentionally created through the application of those layers. Several layers of different-colored lacquer are applied, but not in the conventional manner of spreading, rather in a specific pattern that creates the eventual surface pattern. |

| Hosting Provided by Pacific Software Publishing, Inc. Copyright © 1998-2015 ENMA |

Back

to Top

|

|